ARCHIVES

|

|

Presentation Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery, 10 July 2010:

Unidentified Fermented Objects

The food department of the National Museum of Ethnology (NL)

Animals transform into meat, plants into vegetables and fruits into vitamin C. Becoming food is the final stage of living matter. Some are privileged to a delay of the foreshadowed end. They gain lifetime by being preserved. But a chosen few turn into objects and will never be crunched between the teeth of any other living matter.

They live anonymous, comatose lives in the hidden food department of a museum.

Delicacies from Siam, 1883: peas, sea cucumber and glutinous rice

Museums collect and preserve objects that are valuable, beautiful and interesting for scientific research. In the last decades food museums sprang up like mushrooms. Single subject food museums (chocolate, foie gras, mustard, ramen, cheese, coca cola), agricultural and seafood museums, they all focus on food from different points of view. But none of them preserve food. They don’t have food collections. The Most Beautiful Oyster is not a real oyster, but an oyster immortalized in paint by Pieter Claesz in 1630. And a preserved pig in a museum collection is no confit de porc, but a Damian Hirst, worth eight million dollars.

A few years ago the National Museum of Ethnology in Leiden invited me to make an exhibition about ‘food and culture’. This was a remarkable invitation, because it meant a break with the traditional display of Japanese paintings, Indonesian batiks, Mexican pottery and other typical ethnographic objects. An alarming decrease of visitors forced the newly renovated museum to change its policy and an exhibition about ‘food’ would hopefully attract a new public.

Objects in European ethnological museums are strongly connected to the colonial and scientific exploration of the non-western world in the 18th and 19th century, an era with an unappeasable hunger for exotic objects. ‘Ethnology’ was a general term for what we consider now as separate disciplines. Palaeontologists, physicians, linguists, historians and ethnographers all made contributions to the study of exotic people and the development of mankind. A great variety of objects and material, organic and non-organic, was collected and shipped to Europe. The first museum in Western Europe for the storage and study of ethnological objects was founded in 1864 in Leiden.

At the turn of the 20st century this generalistic view changed. Ethnology disengaged itself from natural sciences and evaluated in a new discipline. Modern anthropology took shape, concentrating on analyzing and interpreting social structures of primitive societies and functional connections between people. The measuring and classifying of the human race gave way to the study of cultures in the world. With this change certain objects in ethnological collections - human remains and all other organic objects - became irrelevant for new anthropological research. They moved to anatomical and natural history collections.

But some survived.

I accepted the invitation and started my research. The images and object descriptions in the museum database gave a first insight into the collection. It was interesting to see that from a culinary perspective the majority of about 250.000 objects - bowls, pots, tools and even paintings - were more or less related to food. Masterpieces like a complete kitchen inventory for traditional cooking from Baltistan (Northern Pakistan), a 19th century wooden copy of a Wedgwood dinner set from West-Africa, an amazingly detailed model of a traditional Japanese kitchen with all the miniature knifes, bowls, pots and pans made from the real materials passed my eyes, and were included in a first selection for the exhibition.

But there was one problem. No food objects were registered in the database. How could I make an exhibition about food without food? Displaying real food together with museum objects was out of the question, impossible. Organic material attracts insects which destroy vulnerable masterpieces. When I visited the museum depots - safely hidden in Second World War bunkers in the dunes near The Hague - for looking at the real objects which I had selected, I discovered that I had missed an interesting part of the collection. Standing back in dark corners there were pots, jars, bottles and boxes covered with dust, with hardly visible and unidentified contents.

A glass jar was filled with a black sludge, labeled ‘Siam’; another one contained moldy, brown balls from ‘Persia’. On an old cigar box someone had written: shark fins.

Nobody had looked after these objects for ages. They formed part of the museum secret food department. Once collected as valuable objects for scientific research, but in the course of years downgraded as irrelevant things, which ultimate date of consumption had passed more than a century ago.

Apparently no other museum had ever shown interest in them. That is how they survived. Without any meddling of museum conservators the contents fermented, dried, molded or evaporated; a process of slow museum preservation that is still going on. Although the conservation department muttered objections – the objects were not described properly which could cause logistic problems – I added them to my list. They belonged to the museum collection, so they were not governed by the rule of not displaying organic material.

Including them in the exhibition also meant identifying the contents of the jars and boxes, where they came from, who collected them and why. Most of them didn’t have the usual museum tags, but the old inventory numbers, hand written on the objects, seemed to be the key to their stories. They referred to more or less famous scientists and explorers or donations from other institutions. In old registration systems and books, carefully kept in the museum library, I found data I was looking for.

Philipp Franz Von Siebold Food Collection

In the 18th and 19th century the Dutch were the only foreigners with permission to stay in Japan. Commissioned by the Dutch East-Indian government, German scientist Philipp von Siebold (1796-1866) collected material for the study of Japanese nature and culture. From 1823 till 1829 he lived in the Dutch settlement of Deshima, a small, artificial island in the Bay of Nagasaki. He was not allowed to leave the island. He could only visit the nearby city of Nagasaki under surveillance by Japanese warders. However, there was this one possibility for seeing more of this unknown country. Every four years the Dutch at Deshima were obliged to visit the Shogun in Edo (Tokyo). Von Siebold made this 5 month long journey in 1826 and took advance of the possibility of collecting objects and information as much as possible. He was interested in all aspects of Japanese flora, fauna and culture, including food. In Kokeno he reported about shobakiri, noodles made of buckwheat, eaten with soya sauce, mustard, onion and red pepper. In Koyanose he sent his assistants to the market for buying as much delicacies as they could get. Among them they bought Japanese crane. The bird seemed to be not only a favorite on Japanese paintings, but also an expensive delicacy. Von Siebold reported that Europeans didn’t like the cooked poultry, served in a soup. His informants gave away that nobody except the Shogun was allowed to hunt on cranes, but that they broke this law regularly.

Seaweed collected by Von Siebold, 1826

When Von Siebold arrived in Edo, he wondered how people fed themselves without having meat, bread and potatoes. He obtained a list of all food products that were available in Edo at that moment (May 1826). The list reports a diversity of products we can only dream of nowadays: 100 varieties of vegetables, 8 kinds of sprouted beans and roots (mojasi), 25 kinds of dried and fresh mushrooms, 20 seaweed varieties, a choice of 70 kinds of fish, lobster, crab and shell-fish, 26 varieties of mussels, 30 poultry and game varieties, 28 kinds of fruit and 12 varieties of grains. Rice is the staple. There is a daily supply of 2 million kilograms. A considerable part is destined for the court of the Shogun, where each grain was carefully examined before being considered good enough for his daily meal.

On his journey to Edo Von Siebold collected seaweed, beans, rice and other grains. He bought different qualities of sake, soya sauce and mustard, together with shiitake-mushrooms, sansho pepper and dried sepia. He also collected green teas in different qualities. Seeds of tea plants were shipped to Java. By packing them in a special way he protected the seeds from drying up during the long journey. The Japanese seeds were planted in Javanese soil, they sprouted, rooted and the Dutch East-Indian tea cultivation became a success.

In 1829 the Japanese government suspected Von Siebold of spying for the Russians. They found out that he had bought topographic maps from Japanese scientists. Subsequently Von Siebold was urged to leave the country. Just in time he shipped all his collected material to the Netherlands. Back in Leiden, he started to organize his collected objects and to analyze his notes and observations. Between 1832 and 1858 he published Nippon. Archiv zur Beschreibung von Japan (Archive of the description of Japan), a Fauna Japonica and a Flora Japonica. Almost his entire collection was bought by the Dutch state. The ethnographic objects became the founding collection of the National Museum of Ethnology in Leiden.

Among them were the food samples. Carefully packed in cardboard boxes, glass jars and original Japanese porcelain bottles, or wrapped in paper.

Food products of the International Colonial and Export Trade Exhibition in Amsterdam 1883.

Delicacies from the Dutch Indies, 1883. First row: dried fish, turtle, squid and emping melindjo

In museum register 1880-1901 is written (in Dutch):

“1884: Donated by H.M. King of Siam, a large collection objects and materials from the Siamese department at the International Colonial Export Trade Exhibition.”

This refers to the 19th world exhibition that took place in Amsterdam from May till November 1883. In the main building countries and trading companies presented their newest inventions and export products. In the colonial section the hosting country exhibited thousands of objects and products from its most important dependency, the Dutch East-Indies.

A few months after the opening a catalogue in French was published that turned out to be full of errors. The subsequent Dutch version showed some improvements, but a complete catalogue of the exhibitions of all participating countries does not exist. A separate catalogue dealing with objects from the Dutch colonies gives insight in the diversity of agricultural products in the Indonesian archipelago at that time. It mentions 104 varieties of rice, 10 varieties of vegetable oils, 40 varieties of flour, 12 bottles of arrowroot from successive years, dried meat (deng deng) from different animals, tropical fruits (nam-nam, madoe, salak and blimbing), ‘Turkish wheat’ (which is probably the same as bulghur), dried shrimp for preparing kroepoek and dried belindjo nuts for making emping. As special delicacies are mentioned: pasiran (sea turtle), mimi (a kind of lobster), troeboek (shad) and other ingredients you’ll never find in a Dutch-Indonesian rijsttafel. To be sure, this variety of products never reached the European market. And meanwhile most of them probably disappeared from local markets as well.

In the catalogue tuna fish is described as not suitable for the European palate because ‘the meat, although tasty and healthy, doesn’t taste like fish’. Special attention is given to Chinese delicacies: dried shark fins, birds’ nests, ebbi (crayfish) and trepang (sea cucumber). It doesn’t forget to mention that the Chinese are willing to pay a lot for an amorphous mollusk that crawls over the ocean floor.

Chinese rice wines and flower essences, 1883

The Staatscourant (official gazette) of November 10 (1883) announced that His Excellency Li Fong Pau, envoy extraordinary and plenipotentiary minister of the Emperor of China has donated objects from the Exhibition to the National Museum of Ethnology. The donation existed of the products Li Fong Pau did not think worth shipping back to China. Among them glass jars, labeled in Chinese and translated in French as ‘Radis doux’ (soft radish), ‘Olive chinois‘ (Chinese olive), ‘Comcombre rouge’ (red cucumber) and ‘lee- chee où guoué–yen’ (lychee). Furthermore green glass bottles filled with different rice wines (Fan-Tsang, Shao-hing and Hing-Tchang, 1st quality) and flower essences. The preservation of the generous Chinese donation has not been very secure. The bottle with rose essence was ‘thrown away because of deterioration by frost’. The sealing wax of two bottles was broken, causing the evaporation of a bottle with flower essence and one filled with rice wine. The paper sealing of the glass jars was broken as well, causing fermented radish and moldy ‘Chinese olives’.

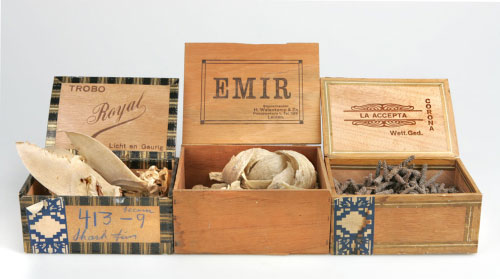

In a small corner of the main building the public could look at products from Siam. King Rama V had shipped ethnographic objects, materials (cobra skin, buffalo horn), minerals and an interesting variety of exotic edible products and delicacies. The Staatscourant (official gazette) of November 22 (1883) announced that King Rama V donated this collection to the Netherlands. The ethnographic objects and the edible products would be added to the national ethnological collection. But not all of them reached the museum. Some were thrown away because they were rotten, tainted, decayed or contaminated during exhibition time. 41 edible objects remained and were registered in 1884. Now, 126 years later, a bottle with ‘best quality cardamom’, a salted fish, a special kind of lard and a box with seeds are missing, but 37 objects are still to be found in the museum depot. Among them the black sludge which can be identified as glutinous black rice, furthermore dried shrimps and mussels, different kinds of peas and beans, lotus seed, fish oil, salt, bettelnuts, pistachio nuts, ‘bastard cardamom’ and long pepper. The Siamese shipment also contained delicacies for the Chinese market: sea cucumber, abalone, fish bladder, shark fins and birds nests. A diligent museum worker repacked some products in wooden cigar boxes marked “Trobo Royal, Licht en Geurig” (Trobo Royal, Light and Fragrant), “Emir” and “Corona/La Accepta”. In the exhibition catalogue all products are named, but the identities of ‘lukrabas’ and ‘duai‘ seeds will probably remain a mystery for ever.

Shark fins, birds’ nests and long pepper. Siam 1883.

An intriguing object from the World Exhibition bears inventory number 503 – 333, a reference to the collection of Albert P.H. Hotz. He was a Dutch entrepreneur who founded the Perzische Handelsvereeniging (Persian Trade Company) in Teheran in 1874. Persia had opened its borders for international trade and the Hotz family started projects in mining, agriculture, banking, tapestry and the opium trade. This company was the first in drilling for oil in Persian territory. Like Von Siebold, Hotz was very much interested in local culture. His inheritance consists of about 15.000 books about Persian and surrounding cultures and a unique collection of high quality photographs which he took himself between 1874 and 1902. Hotz wanted to sell his Persian products and therefore did send a selection of them to the Exhibition in Amsterdam. Among these were food samples that the museum bought after the exhibition was closed. The glass jar labeled as ‘milk’, is mentioned in the exhibition catalogue as kechk, which we can identify now as kashk or sun-dried buttermilk balls, which are still common in Iran for making a sour drink or as a binder for soups, sauces and stews. Hotz’s choice of Persian culinary products was rather inscrutable. Number 503-333 is a glass jar filled with the ‘stomach of a lamb’. Why he selected this organ together with bitter almonds, chickpeas, riceflour and ‘mixed seeds’ in stead of Iranian cuisine highlights like rice, sheeptail fat, caviar, saffron, dried fruits, dates, pistache nuts and essences from fruits and flowers, is a question that probably will never be answered.

Jar with ‘melk’ (milk), 1883.

It refers to Persian kashk: dried milk balls. After the milk is skimmed, it is sun-dried. The balls are dissolved in water for making a sour drink or they are used as a binder in sauces, soups and stews.

Gottlob Krause’s West-African Food Collection

As an opponent of colonialism and slave trading, German linguist Gottlob Krause (1850-1938) became the enemy of the German government who tried to obtain colonies in Africa. In the 1870’s he was sent to an area in West-Africa that was still ‘free’ for foreign domination. When he found out that his linguistic and ethnological research was a cloak for preparing the German colonization of this part of Africa, he immediately refused all cooperation and started publishing articles about the colonial intentions and misbehavior of the Germans in Africa. In 1888 he returned to Africa, this time as representative of an ivory trading company in Stuttgart, as well as for studying languages and collecting ethnographic objects in Togo, for his own sake. Needless to say that he did not offer his collection to a German museum. In 1889 the museum in Leiden bought his collection consisting of 1700 objects. Krause had bought many of his objects at the market in Salaga (Ghana). The edible part of the collection consists of twenty glass bottles filled with a variety of dried beans, rice, vegetables, fruits and flour. The non-preserved, perishable African fruits and vegetables have transformed into moldy and unidentifiable food objects. Unfortunately there is little information left about his food collection. After his death in 1938 nobody was interested in his notes and archive. They ended on the scrap heap in Zürich, the city where he past his last years.

Gottlob Krause food objects. West-Africa, 1888.

Dr. A.G. Vorderman’s Edible Earth Collection

Geophagy is the word for eating earth or clay. In 1891 Dr. A.G. Vorderman, health inspector in the Dutch East-Indies, donated a collection edible earth to the museum. In his manual for comparative ethnology of the Dutch East-Indies, Dr. G.A. Wilken writes about eating clay: ‘Many wild and semi-civilized Asian tribes, Negros tribes in Africa, American Indians and even people in South- Europe eat clay’. The Javanese distinguished different kinds of ampo, which they prepared with great care. First they washed the clay and removed sand and stones. After soaking it an overnight in water, the clay was kneaded into flat cookies or small pipes. Then they were salted and finally roasted.

Wilken writes that people eat clay, not only when they are very hungry, but also because it contains healthy minerals. If it is darkish red, it is full of iron and specific kinds of clay contain salt, calcium and magnesium. Pregnant women all over the world eat clay. In Java women told Wilken that it helps against sickness in the first months of pregnancy. He also discovered that the miners of the Oranje-Nassau Mine on Borneo changed their opium addiction for an addiction to clay containing 28% bitumen: ‘…their faces are pale and swollen; their eyelids are inflamed. They are lethargic, constipated and because of that melancholic as well.’

G.A. Vordermans collected forty samples of raw and cooked clay from different parts of the Dutch East-Indies. The raw clay samples are still wrapped in the original brown paper; the roasted clay cookies are kept in glass jars. All of them still have the original hand written labels with the location where the clay is found.

Clay cookies and raw edible clay, Dutch East-Indies, ca. 1890

All food objects described above have been on display in the Food & Culture exhibition at the National Museum of Ethnology in Leiden in 2007/2008. Unfortunately I could not stop the conservation department from cleaning the jars and boxes, so they lost part of their inherited charm. The edible clay, the jars with fermented sludge and a set of mysterious vegetable oils from Indonesia were the eye catchers of the exhibition, together with dried insects imported from Mexico that people could taste and buy at the museum shop. The new visitors the museum had hoped for came, but the regular visitors stayed at home, so the total amount of visitors did not increase that much.

Now the food objects are placed back in the depot. For the time being nobody will bother them again. Recently a few succeeded in getting a proper place in the museum database, but the majority returned to their anonymous and comatose existance.

But now their lives as museumobjects are in danger again. The National Museum of Ethnology is tidying up her chock-full depots by ‘de-selecting’ objects that are not worth preservation or restoration. Sooner or later the food objects will be noticed again. Modern curators are not interested in matured soy sauce, whether or not fermented over the ages. Nor in the flavors of different qualities of 200 year old Japanese green tea, let alone in the smell of a sea cucumber that has been locked up in a jar for 127 years. Even museums don’t preserve for eternity.

But before their lives as food objects end definitely, without ever being tasted or smelled by a human being, I will preserve them as digital photo pixels, with a history.

References:

P.F.von Siebold: Nippon. Archiv zur Beschreibung von Japan. Leiden, 1832 – 1858

Catalogus der afdeeling Nederlandsche kolonien van de Internationale Koloniale- en Uitvoerhandel tentoonstelling te Amsterdam. Leiden, Brill 1883.

A.G. Wilken: Handleiding voor de vergelijkende volkenkunde van Nederlandsch-Indië. Leiden, 1883

www.volkenkunde.nl

|

|

|